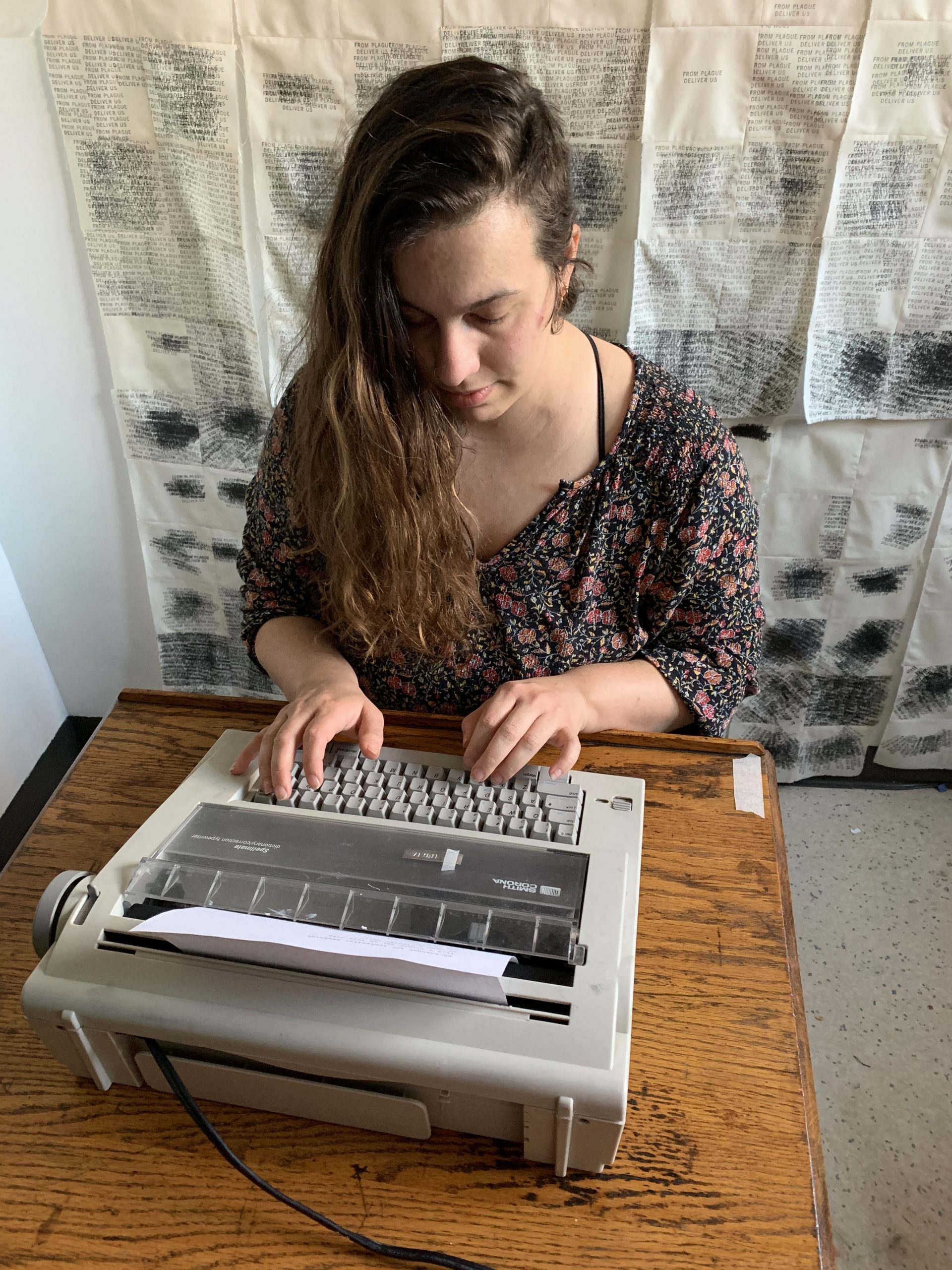

Thanks to our Sputnik Patrons, we’ve given a grant to visual artist Elizabeth Kwant. Elizabeth is a Manchester based artist, researcher and curator, who focuses her work on highly raw social issues such as colonialism, immigration detention, and modern slavery.

Her new film, ‘Volta do Mar’, continues that journey closer to home; a meditative performance focused on the interwoven histories of peoples and places in the UK, and the trauma that we find there. We asked our good friend Ally Gordon, from Morphe Arts, to find out more. We were really struck by Elizabeth’s work, and really happy that we could help bring this next piece to the finish line.

Making collaborative work, retelling important stories, and facing up to the demands of social justice are priceless processes. Why not join Patrons scheme for as little as £5/month, and we can give out more micro-grants to artists like Beth, who are taking risks to make difficult work.

Can you tell us a little about your new project, ‘Volta do Mar’?

I’ve been working on this project for a few years now, in an ongoing way. Let me backtrack a little bit to explain where I came from! Back in 2018, I spent a year in the archives of the international slavery museum in Liverpool. I spent time looking into the legacies of transatlantic slavery in the North-West of England.

So looking at the compensation which followed abolition – those plantation owners who received money for slaves; and where did that money go, basically?

That project culminated in a moving image installation, in the museum, in the transatlantic gallery, which was co-created with female survivors of modern day slavery. Through the process I had been looking at trauma, and how we hold it in our bodies; I really wanted women who had experienced a similar trauma to be able to respond to that history through their own stories.

During that time I did all that research, and in some ways it was behind the film but didn’t translate into the film itself. I wanted those women’s voices to be heard, so I didn’t go too deeply into the history around it. So I came away with all these ideas brewing! Volta do Mar comes from that period of time, where I had been researching into Cumbria, where I’m from originally – I was born in a small town called Whitehaven.

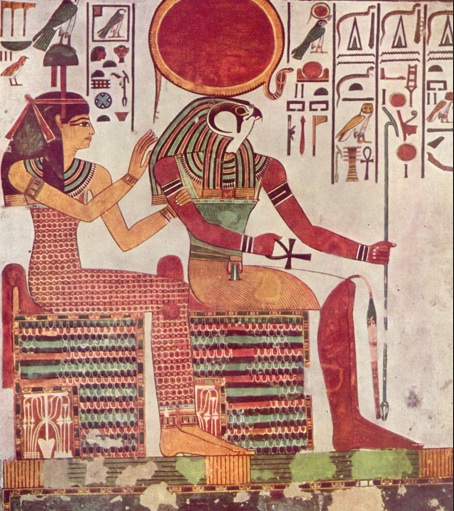

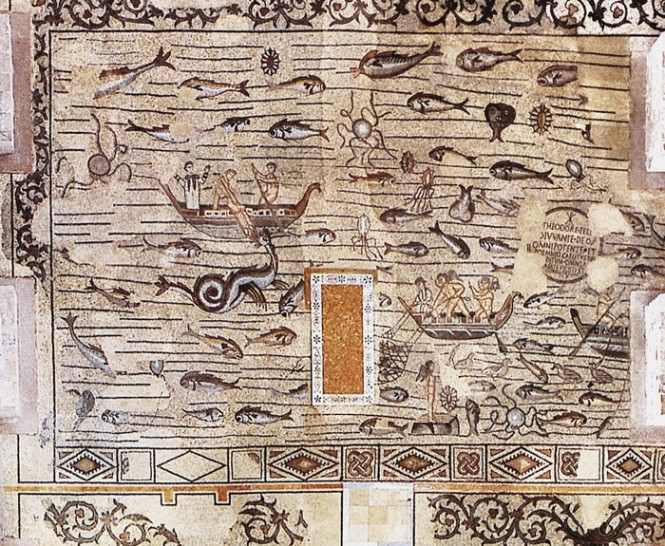

As I began to look into the history of colonialism in Cumbria, I realised that Whitehaven was one of the most important port cities in the 18th Century, in the UK, for the trade in tobacco, and later sugar.

Often when one thinks about slavery in the UK we think about Glasgow or Bristol – so that’s an interesting part of the history in Britain.

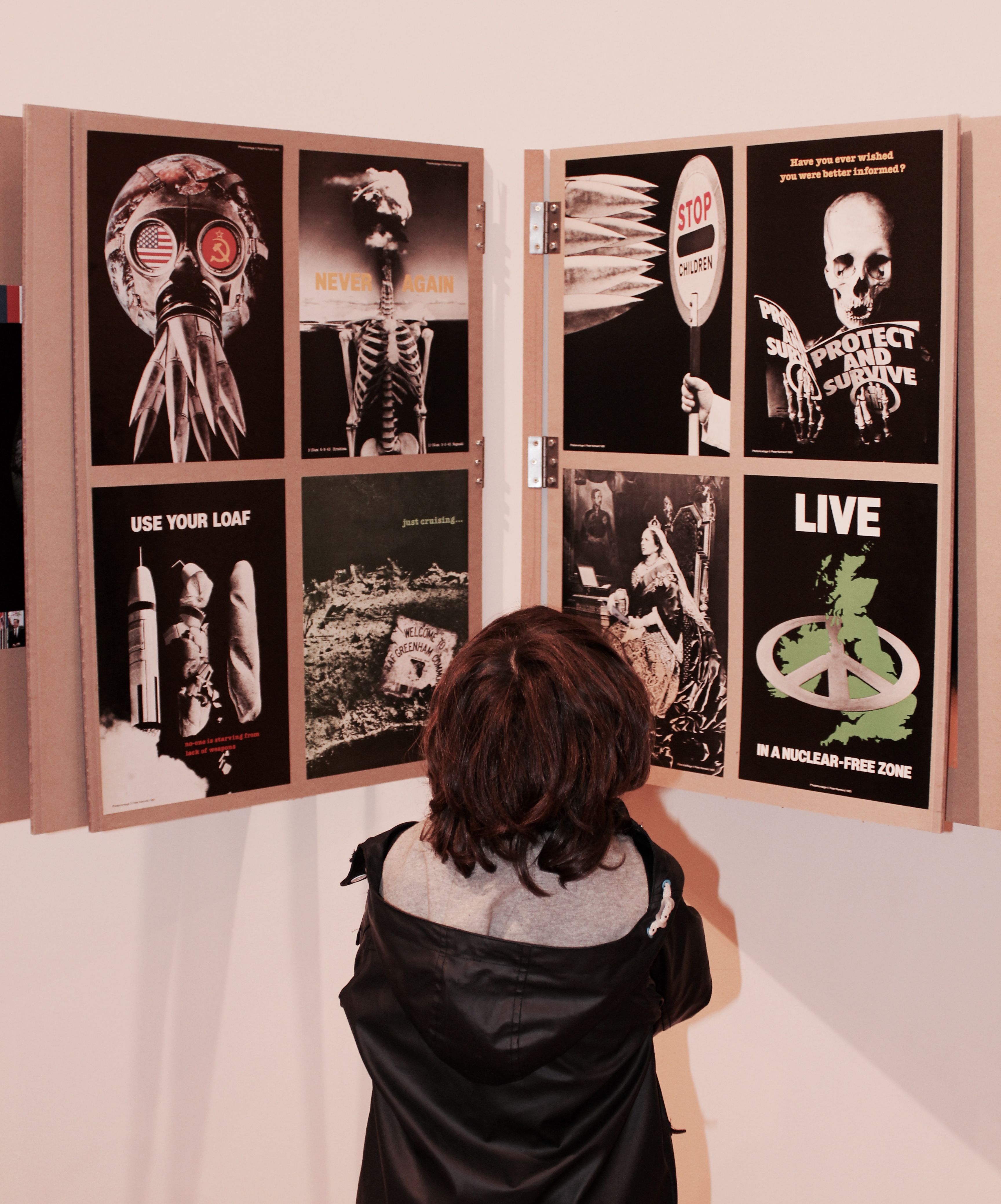

I think with Cumbria you think of holidays, lakes, the National Trust, the picture perfect postcards! Interestingly I’ve come up against a reluctance to even look into this history, from institutions, tourist sites, even locals in some ways. Across the UK there’s an amnesia about that time in history. It’s generally not taught in schools. So I felt I wanted to somehow perform in some of these locations and places, and bring a kind of embodied presence into those spaces – particularly focused on Whitehaven.

How do you hope this project will help to highlight this part of history?

I think things work on multiple levels with art; often we’re told things in books or in a lecture style, quite a didactic way. I think artwork creates a space to engage with ideas on a heart level, an emotional level.

I really hope that my work does that, the moving image installations that I make do create a physical space as well; I like people to go in and experience the work, I particularly don’t like showing work on a cinema screen, that sit-down, flat, passive experience.

The last piece I made was in a circular room, and people walked in and were surrounded by women who were survivors of slavery, but who were on eye level, so they were engaging with them on an equal par.

It makes me think how art can open a space to discuss things that otherwise we can’t talk about; or to exist in a liminal space where we’re being intuitive over ideas that are difficult to comprehend.

There’s the personal aspect where I’ve been grappling with this as a white Brit; how do I authentically look at these histories in my work? Do I even have a right to? Some would say I don’t, and these issues are really complex. That’s why in the past I’ve chosen to work more collaboratively.

It’s wonderful to hear that Ruth Naomi Floyd is involved in the project, and of course Ruth often sings about her personal family story and her great great grandmother, who was treated truly awfully. Her music brings me to tears! Can you say a little more about that involvement?

I heard Ruth play the jazz flute recently! I’d been up in Cumbria filming, and thinking about the sound; I knew that I wanted to layer sounds. I really love working with found sounds; I wanted the sound of the mining machinery, because it was the coal mines in Whitehaven that exported coal to Ireland, and collected slaves from Africa afterwards. And the sound of the Solway Firth which is the sea there, next to the town.

So I have these layers of sounds that provide a base. When I heard Ruth play, it was just very evocative and emotive, and I thought that’s it!

I really love to be able to collaborate with an artist of Black American heritage, whose family history is linked into the history of slavery; and also somebody who is such a wonderful advocate for racial justice. I can’t think of anybody better to put sound with the film.

So Ruth is going to be composing jazz flute. It won’t necessarily be vocals. She’ll be responding to my performances in the sites. The film is, I suppose, about lament, and in places quite ritualistic. Ruth will be responding to the history of the sites, and also the visuals of the film. And we hope that later in the year she’ll be able to actually visit the sites and respond more emotively to the history of the places.

It strikes me that a work of art of this nature, a performance of film with music, is less didactic, less instructive, but speaks to true events and can be a way to talk about things which are true, in an emotive way. Would that we had more lament in the world!

To find out more about Elizabeth and her work, follow her on Instagram, or see her website.