We as the Western Church have our own brand of art. It is relatively safe, clean, and historical. Though often kitsch and sentimental, it draws from the giants of western art history like Giotto, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt. A brief survey of art history according to any well-known publisher reveals Biblical scenes and gospel illustrations aplenty.

With this established history behind us it is tempting for both the Christian artist and art-viewer to refrain from engaging with creative culture beyond our little world. Anything outside of the church’s output can be considered ‘worldly’ and ought to be avoided: all the more so if it contains themes or motifs that are distinctively ‘non-church’.

As an example, for many Christian communities Harry Potter is an absolute no-go. Despite the narrative following the chosen one who overthrows the illegitimate rule of the dark Lord, Christians will often complain that there is too much ‘darkness’ in the series. All that realistic talk of magic and ritual is too close to the reality referred to (ED: I wonder whether the same thinking is behind some Christians’ negative reaction to Doctor Strange).

In this post I want to look briefly at the origins of some of the Church’s ‘safe’ art motifs. As we’ll see, ‘Christian art’ is not quite as ‘Christian’ as we often think and this raises some important questions for Christians making art today.

The early church and the artists who laid the foundations for our brand of Christian art were an eclectic bunch of folk whose unity was found in their faith alone. The first artists in the church found themselves in a cultural Babylon. Naturally, styles and attitudes towards art varied greatly, and with no uniform Jewish art source to draw inspiration from, ‘Christian art’ drew heavily from pagan influence.

Though today we as Christians can prefer work that is sanctified by our particular publishing houses or church record labels, the first Christians had no ‘clean’ art before them. All surrounding and indigenous artistic culture was ‘pagan’: it didn’t represent the monotheism they had inherited from Judaism, and yet as the church began to meet in a increasingly pictorial world, murals and icons soon emerged in their communal places.

The early artists didn’t shy away from the pagan art around them but selectively chose elements from the Roman and Greek world to appropriate into their own in order to effectively communicate the new truths of the Gospel through the old systems. I imagine that the norms of the art world were the letters with which the early artists began to write new words.

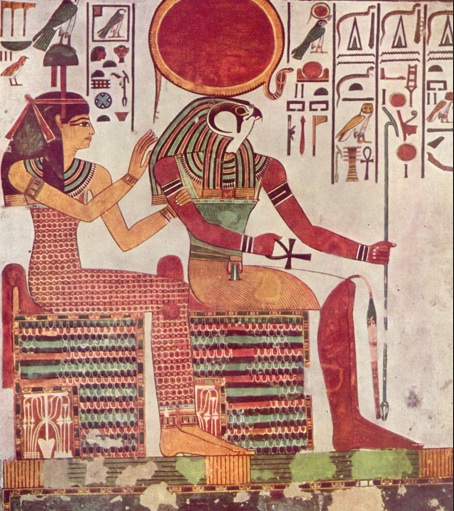

Many of our current ‘Christian’ motifs actually originate from this early cross-cultural borrowing. The halos we expect to see enshrining the heads of Christ and the saints seem to have been created in ancient Egyptian times to denote Ra as the sun god and found their way into the Middle East through depictions of the Roman sun god Apollo (there is no mention of haloes in the Bible).

Another interesting appropriation by the early Christians is the Good shepherd motif. Though we can affirm with certainty that Jesus would have been an almost middle aged bearded Jewish man at the time of his ministry, the earliest ‘good shepherd’ images saw a clean-shaven Yeshua in Roman clothing carrying a sheep over his shoulders (even equipped with pan-pipes on occasion). The now certified-Christian image borrows heavily from the legend of Orpheus and possibly the Moscophorus Calf-bearer image, but within its own system of meaning, it referenced the young King David from whom the Christ King descended.

As the early Christians looked at their surrounding culture they didn’t just see a debauched world in need of salvation but a whole realm of images that could be used to better communicate their message to all nations. It can be argued and has been argued that Roman and Greek art forms were heavily borrowed under times of persecution so that the early Christian congregations would not be betrayed by their catacomb arts. However, even after Constantine’s conversion, pagan motifs were being assimilated into the church’s oeuvre: for example, winged angels only appear in Christian imagery after 313AD.

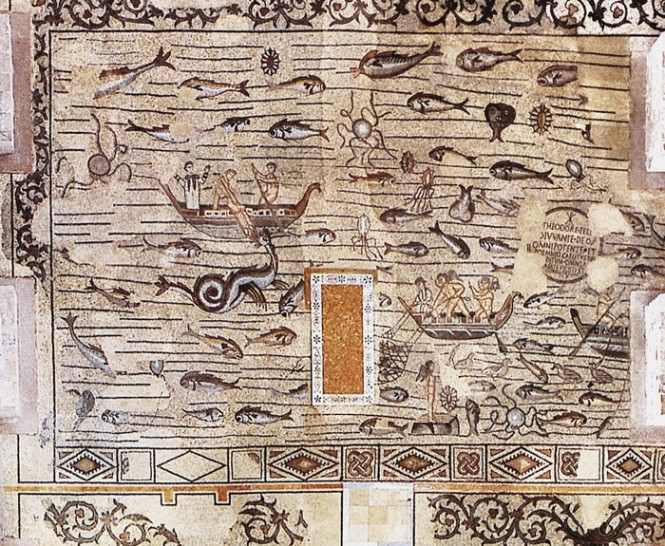

But the likenesses didn’t just stop at the visual. The early artists were also theologians who found similarities in the Christian, Jewish, and Pagan stories. In Greek mythology Endymion was a youth who perpetually slept under the protective love of the goddess Selene. Depictions of Endymion soon became the prototype for images of Jonah lying under God’s protective gourd: this then evolved into a reference to Christ’s descent into hell and his story of salvation for the Gentile world.

One of my favourite works of the early church is found on the floor of an early Basilica in Aquileia (Italy). The image sees the whole story of Jonah depicted as one scene, the prophet lay under the gourd while simultaneously being spewed out of a mythical creature’s mouth. The seascape is alive with realistic fish of all kinds, octopi, ducks, and even some fishing cherubs. The vast work would have required great forethought and planning, and though we may not understand all of what has been handed down to us, I can still marvel at this design as a work of brilliance. It is both fully Christian yet fully ‘pagan’ (not-Christian in our understanding of historic Church design).

You may now be wondering where I am going with this. It is not my intention to discredit the early church artists, but quite the opposite. I believe that the versatility of the craftsmen and their openness to the neighboring world helped them envision a universe where all people could find the Christ in all things. It is not universalism or heresy to see the type of Christ in creation and humanity’s interpretations of it.

In fact, C. S. Lewis argues that this is exactly the type of world we should expect to find, writing,

“We must not be nervous about ‘parallels’ and ‘pagan Christ’s’- they ought to be there – it would be a stumbling block if they weren’t.”

Lewis argues that the myths of pagan cultures (and we could add the stories of superheroes and villains of our times) could have acted as a

“preparatio evangelica, a divine hinting in poetic and ritual form at the same central truth which was later focused on and (so to speak) historicized in the Incarnation” (from essays Myth Became Fact and Religion without Dogma).

My questions are:

Is there a place to borrow the contemporary ‘pagan’ images found in the arts in order to more effectively communicate what we have received?

If so, how can we as Christians appropriate from the world around us in order to create words that rightly convey the mystery of the Christ?

[…] some Eastern symbols in the work). Ben replied by linking his digital conversant to his excellent Sputnik article on pagan art and Christian art. There was a pause in the thread, and a few minutes later, Ben’s friend replied with continued […]