Thanks to our community of Patrons, we’re helping to fund a research project by typewriter artist India Johnson. One of her inspirations is Dom Sylvester Houédard – a monk, theologian, and concrete poet. India discovered that DSH’s archive of work had recently been transferred to the exact town where she lives – giving her the unique opportunity to delve into his work first-hand, and produce her own artworks in response.

We love to support artists like India, who are engaged in deep dialogue with culture and their chosen artistic practice. Why not join our Patrons scheme for as little as £5 / month – and we can keep supporting great projects like this.

Hi India. Can you introduce us to yourself and your work?

My background is in hand bookbinding. My first formal bookbinding study was at the LLOTJA Book Art Conservatory in Barcelona. Eventually I landed at the University of Iowa Center for the Book in 2017 for graduate studies. I still live and work in Iowa.

In graduate school, one of my professors took us to study some early christian books in libraries in Chicago. They were some of the oldest and most beautiful manuscripts I’ve handled, written in Greek. Handling a prayer book from the middle ages can be a very intimate and meaningful experience, even if you can’t read the text. Touching these precious, ancient devotional books prompted me to shift my focus from bookbinding to making contemporary pieces. I wanted to make work that echoed the experience of holding a sacred book in your hands.

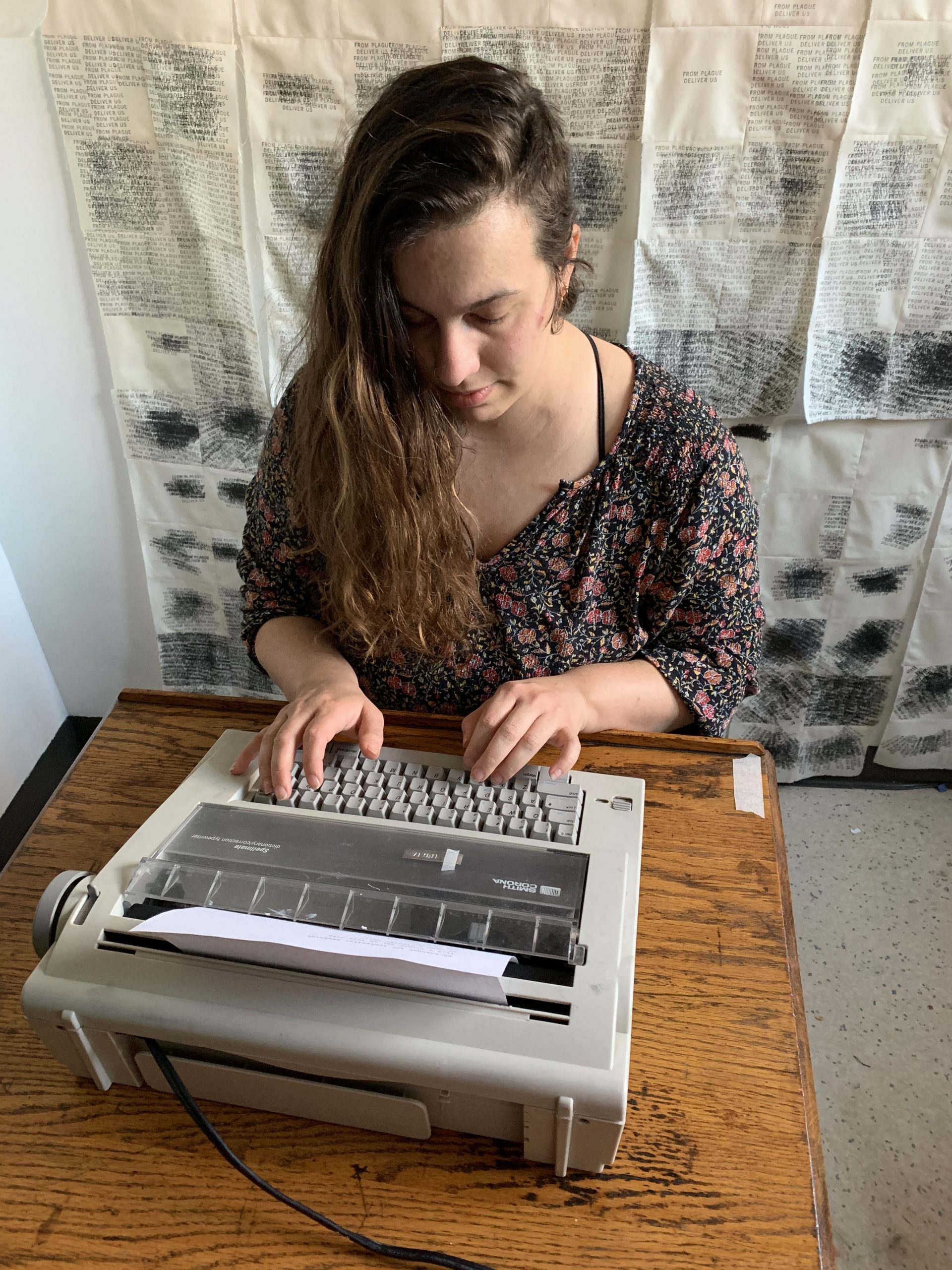

I work with delicate materials, mostly paper and cloth, to create sculptures, books, and textiles–often with christian texts. Throughout the pandemic, I’ve mostly been working with text from the Book of Common Prayer, which was compiled during a plague. I also like to work with the King James translation of the Psalms. It’s the first example of blank verse (poetry without rhyme or meter) in English. My work visits and re-visits these canonical texts because mystical and spiritual experiences happen both despite and within established social structures.

I prefer to exhibit my work in settings where it can be handled; mostly churches and libraries. How much of reading is touch?

We are delighted to be supporting you on your new project through our patrons scheme. Can you talk us through it?

Many of my pieces use a process for running cloth through a typewriter. The artist who most directly inspires this work is Dom Sylvester Houédard (abbreviated as ‘dsh’). He was a Benedictine monk and a poet. dsh is best known for a body of intricate, abstract typewriter art produced from the 1940s to 70s. When I first looked into dsh’s work, all image credits pointed to a private collection, the Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry. I decided to plan a visit–and discovered the collectors had just donated the entire archive to the university in the town where I live. What are the chances? It felt like more than a coincidence. Sputnik is funding a few months of research sessions with Dom Sylvester’s papers, which include beautiful examples of his typewriter art, as well as some correspondence and scholarly writing. I’ll be producing artwork in response to Dom Sylvester’s archive; the medium will be typewriter on textile.

Dom Sylvester sounds like a fascinating man. What drew you to him for this project?

When I first started making typewriter art, I would be at the machine for hours, typing the same fragment of text over and over again. Even though I was working with familiar texts, like the psalms, through all the repetition, the language would become totally abstract for me. More abstract than I knew words could be – being something rather than meaning something. I really came to understand prayer first and foremost as an experience of language. Dom Sylvester’s typestracts show how language can become a thing in itself. When we push words past what they mean, past signification, we come to understand something about the relationship between embodiment and transcendence. One thing that’s become clear since starting my research is that the typestracts are generally smaller than I thought they would be. The paper is very light–almost translucent, but not quite. The typestracts feel so delicate and intimate and focused; they’re a wonder.